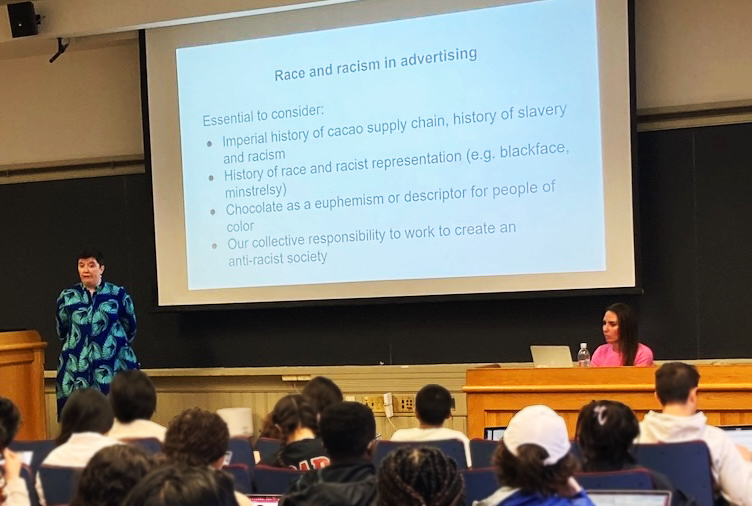

On a Thursday afternoon in late March, social anthropologist Carla Martin begins her lecture with a warning that might seem out of place at first in a course all about chocolate, one of the most delicious and beloved substances in the world. “You’re going to see some images that are explicitly racist and explicitly violent,” she tells the students, who are still settling into their seats in a first-floor classroom of Sever Hall, opening up laptops and notebooks, while the last stragglers tiptoe in at the back and scan the rows for an open chair. “So it’s important to be prepared for that,” Martin continues. “It’s important that we recognize these images for what they are, that we are able to perceive and analyze them.”

The students, a mix of undergraduates and Extension School enrollees (some joining via Zoom), don’t seem surprised. It’s week nine of the semester, and in Martin’s popular course, “Chocolate, Culture, and the Politics of Food,” they have been learning a lot about the dark side of the “food of the gods”: the role of colonialism and slavery in cocoa production, the myths the industry often perpetuates about purity (in both food and people), the environmental fallout of extractive approaches to nature, and the politics behind the rise of “big chocolate” and the global market. A week ago, students were reading about modern-day child labor in Ghana’s cocoa fields. The week before that, about Gilded Age magnates like Milton S. Hershey, whose vast factories transformed chocolate into a mass-produced industrial food. Today’s lesson is about advertising, and how racism and sexism are used to sell sweetness.

A lecturer in African and African American Studies, Martin first taught this course in 2013. She’d been asked to come up with something that could attract students who might not otherwise find their way to the department, and chocolate seemed like a promising and obvious possibility. People always perk up at the mention of it, and chocolate offers a strikingly effective lens on big ideas like slavery, colonization, power, and morality. Plus, Martin, the founder and director of the Fine Cacao and Chocolate Institute, had a scholarly interest in the subject. After college (she earned bachelor’s and master’s degrees in social anthropology at Harvard, before later returning to the University for a 2012 doctorate in African and African American Studies), she’d spent several years in Cape Verde, off the west coast of Africa, where she studied Portuguese and taught school and lived with a local family. One year, she traveled with legendary Cape Verdean singer Cesária Évora. “A completely transformative experience,” Martin said in an interview. “It led me to my Ph.D. program.”

While she was there, she also learned about the country’s tangled history with chocolate. For centuries, that meant enslavement and forced labor. But even as late as the 1960s (Cape Verde gained independence in 1975), Portuguese colonial rulers were conscripting Cape Verdeans, loading them onto boats, and shipping them off to work on the cocoa and sugar plantations in South America. “After abolition [in 1878], the way they replenished the labor supply was through these nefarious contracts, in which people were more or less indentured laborers,” Martin said. “And all of the same problems we see in the history of slavery occurred in that labor system: people would run away, people would have strikes and rebellions. There were often hospitals built on these plantations because people were so ill from the work.” Finding out about all this, Martin remembers feeling shocked. “As a lifelong chocolate lover, I was really interested in how this important raw material could be produced under such abhorrent conditions, while at the same time, for me, it was a cheap, fun thing to have. That really drove me.”

The first year she taught what has come to be known as “the chocolate class,” she expected an enrollment of 16 students; instead, more than 200 people signed up. In the years since then, attendees have included Nigerian cocoa producers, Starbucks executives, and a number of food journalists (the class has occasionally received less welcome attention from white nationalist bloggers). The current syllabus includes numerous films and scholarly readings and online “explorations,” but it’s anchored by three main texts: The True History of Chocolate, by married anthropologists Michael D. [’50, Ph.D. ‘59] and Sophie D. [’55, Ph.D. ‘64] Coe; Amitav Ghosh’s The Nutmeg’s Curse: Parables for a Planet in Crisis; and Sweetness and Power: The Place of Sugar in Modern History, by food anthropologist Sidney Mintz.

At some point during every semester, Martin treats students to a tasting, in which she counsels them on how to evaluate not only the taste of different types of chocolate, but their look and feel—and sound—as well: the crisp snap when one breaks off a piece of a high-cacao bar, the softer thunk of milk chocolate. “From the beginning, the thinking was, what if we had the promise of chocolate samples,” she said, “and then once people came in the door, we hit them with the heavy stuff.”

In today’s class session, the heavy stuff begins with a PowerPoint slide of an advertisement from the 1940s, for Rowntree’s Cocoa, a British brand (and the creator of the better-known Kit Kat bar). In the ad, a black little girl in a polka-dot dress, with pigtails and exaggerated eyes—a character named “Honeybunch,” Martin informs students—holds a steaming cup of hot chocolate. “Feelin’ kinda hungry?” she says to a bird pulling a worm from the ground. A tagline at the bottom reads, “So grateful—so genial—so GOOD.” Everything about the image, from the girl’s caricatured eyes to her non-standard English to the not-so-subtle suggestion of how she should behave (grateful, genial), piles stereotype onto stereotype, Martin explains. “There are so many images like this,” she says, clicking over to the next slide, from the same era, which shows a magazine advertisement for a type of cupcake literally called “Chocolate Pickaninnies.” (Two for five cents!) Two grinning disembodied African faces float off to the side, their eyes turned comically upward, their heads covered in wiry braids.

Martin looks out at the students to gauge their reaction to the pileup of stereotypes. “Is that clear?” she asks. They nod. It’s clear.

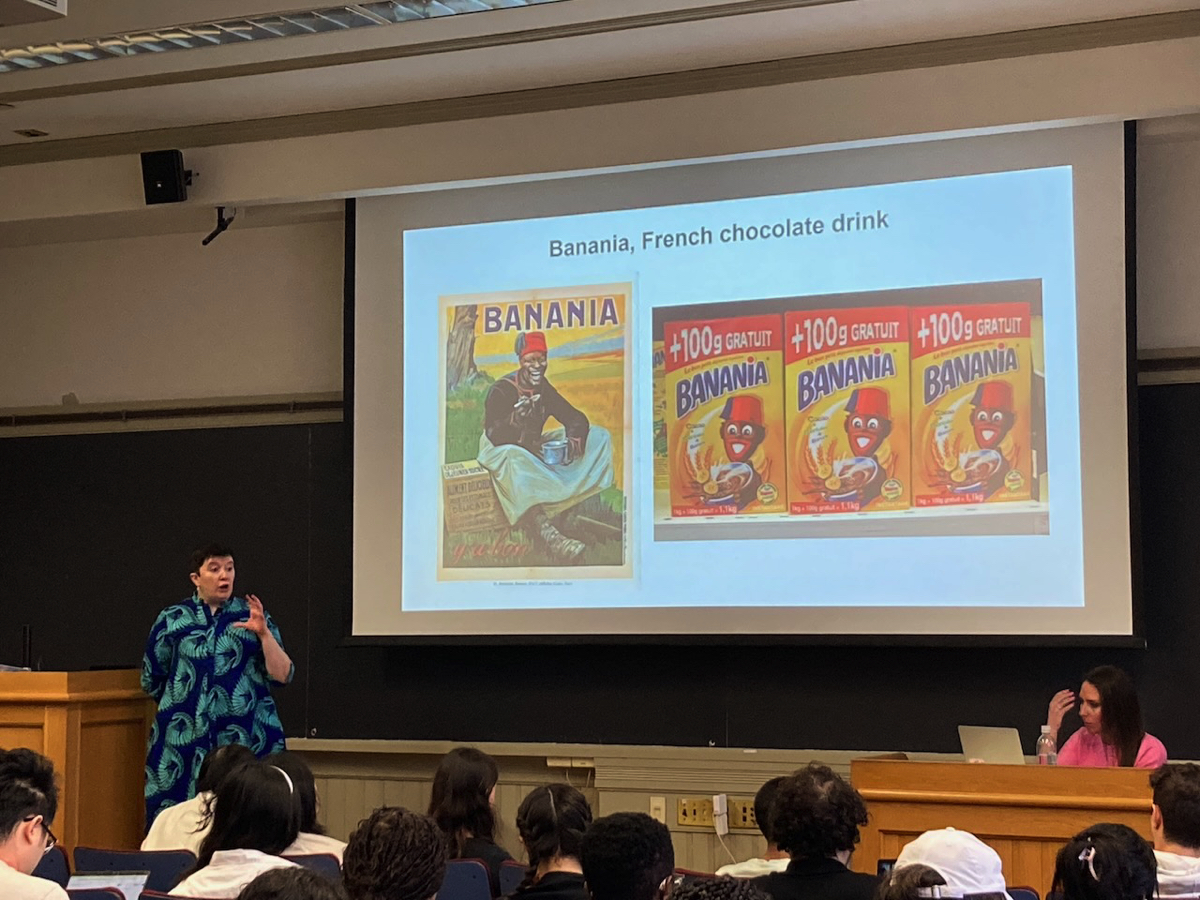

Another image, and then another. Martin shows the class a 1915 advertisement for a French chocolate drink called Banania, which is still widely distributed. A black man wearing what looks like colonial infantry uniform—a red cylindrical cap, a rifle at his feet, an African landscape behind him—sits on the ground with a childlike open-mouthed smile, a spoonful of the drink in his hand. “Y’a bon,” the tagline reads, a pidgin French expression that means, “It’s good.” Next, Martin displays the current Banania logo, “which you can find on grocery store shelves today,” updated recently in response to complaints of racism. The man’s lifelike image has been transformed into a cartoon one, but the ethnic hat, bulging eyes, and childlike smile remain. A few students shift in their seats. Martin nods. “Not a lot better, huh?”

Another image: a Spanish chocolate candy called Conguitos (the name means “little Congolese”). “Have any of you seen these in Spain? They’re everywhere,” Martin says. “They’re like M&Ms of Spain.” The candy is round, and the mascot character is a small rotund figure with brown skin, wide eyes, and huge red lips. Martin queues up a television commercial: over the rhythm of jungle drums, a group of Conguito characters, dressed as tribesmen, carrying spears, and shouting gibberish, run for their lives through the forest. One by one, they are plucke from the ground by a huge white hand, and eaten. Pressured in 2020 to rebrand, the candy company introduced … a white chocolate version of the same Conguito character. Seeing it, some students laugh. “I can see that you’re all shocked,” Martin says.

There are more examples of similar ads—hundreds more, she says, as many as anyone could bear to look at: crude stereotypes, blackface, minstrelsy. To demonstrate that such racist imagery isn’t only centered on black people, Martin pulls up an advertisement for a Swedish brand of puffed rice dipped in chocolate. On the package, which is yellow, an exaggerated Asian face smiles under a pointy conical hat, mouth stretched wide, eyes so slanted they seem to be closed. Martin walks the class through a discussion of the tortured, sometimes unintentionally hilarious evolution of the Oompa Loompa characters from Charlie and the Chocolate Factory. Each new update is somehow more absurd than the last, as filmmakers or illustrators tried to reimagine and redeem the characters that Roald Dahl first depicted, straightforwardly, in his 1964 children’s novel as pygmies imported from “deepest and darkest” Africa (on a ship!) to work in Willy Wonka’s chocolate factory.

Finally comes the moment that Martin was warning about at the start of class. She clicks over to a slide with a photo collage of black people—men, women, children, adults—each missing a hand. They’re posed, seated, draped in white cloth, looking straight at the camera. In another photo, two white men stand with arms crossed, and in between them, a group of scowling African men hold up severed. In Congo’s long and violent colonization, Martin explains, Belgian rulers would punish stealing, disobedience, and other misbehavior, by cutting off a person’s hand. “There are people alive even today who remain maimed by this practice,” she says. And, she adds, “Belgian soldiers would actually send baskets filled with decaying hands back to Belgium as evidence that they were policing the local population.”

She pauses a moment to let this sink in. Then she moves to the next slide: a photograph of hand-shaped chocolates, a traditional product from the Belgian city of Antwerp, whose symbol is a hand. Someone in the room gasps. Locals trace that hand symbolism to a legend about an evil giant who lost his hand to a Roman soldier (who saved the city), but Martin explains that the hand-shaped chocolates are connected to colonial history. “This practice in the Belgian chocolate industry did not exist until this practice took place in Congo,” she says. “This is established; it’s been well-studied by anthropologists. And I think it’s something that we must reckon with in relation to cocoa and chocolate.”

Off to the side, a teaching assistant pipes up, with a comment from a student participating via Zoom. “I have someone in the chat saying they’ve been to Belgium and they bought some of these hands and did not realize, and they feel awful.” A pause. “But that goes to show, that you can be buying products and not know the history. You’re just buying products.”

“It’s a cultural blind spot,” Martin says. “Belgians every day go and purchase these, and most people are not aware of the history. It’s been purposely written out.” This kind of history—obscured, forgotten, complicated—is what the class is all about. How consumption and exploitation intertwine in ways that are so deep and fundamental that they’re hard to see.

The discussion continues for another 20 minutes, with Martin opening up a whole new series of slides on gendered discourse and the myriad ways chocolate advertising fetishizes housewives and mothers, and depicts women as seductresses or seduced in the presence of chocolate. “They advertise chocolate as though it is, quite literally, sex,” she says. She shares a collection of stock photos, compiled by a previous student, of women and chocolate in erotic poses—eyes closed, lips open, their bodies sometimes smeared with the melted substance. “My understanding from people who work with chocolate,” she quips, “is that this will give you a terrible rash.”

She closes the class with a few examples of chocolate advertisements done right: usually by companies in Africa or South America, locally owned by people of color, often showing workers in the midst of their labor, looking thoughtful, dignified, relaxed, in control. But the shocking sight of those Belgian hands—the tidy chocolates in a box juxtaposed with the photos of missing limbs—lingers. After a while, Martin looks at the clock. “Is it time?” she says, before passing out the day’s planned quiz. And as her students pick up their pens and turn toward their laptop keyboards, the classroom falls into concentrated silence.

Martin also provided remarks on the ongoing cocoa crisis affecting farmers, supply chains, and consumers. Watch the full interview on YouTube below: